|

Page one / Page two

/ Page three

Whilst at the time the whole video nasties furore seemed extraordinary,

in hindsight it should have surprised nobody. The Establishment

has always viewed new media, particularly those embraced by a younger

generation, with a great deal of suspicion. Obscenity trials against

theatrical shows like Oh! Calcutta and the satirical magazine Oz

in the late 1960’s provide a depressing nod towards the events

of the early 1980’s. These moral whirlwinds also blow up during

times of acute social or political difficulties, so when the new

media of video finally began to gain mass acceptance in the early

1980’s, a time of high unemployment, race riots, economic

recession and rising crime, the scapegoating of videos as public

enemy number one was almost destined to be. The whole episode is

also a salutary lesson in the power of minor interest groups to

inform public policy, providing they have powerful friends and are

prepared to embellish the facts with a healthy dollop of hysteria.

The fact that the video industry, in its infancy in the UK and

effectively unregulated, did itself no favours with lurid advertising

campaigns and publicity stunts is beside the point. The explosion

of video ownership created hundreds of new labels, often operating

out of garages and tiny provincial towns, that were unable to acquire

the rights to big-budget Hollywood movies so, in order to service

the growing demand for videos, ended up releasing material that

had never previously been released in the UK. Today, the market

is dominated by the video arms of the major Hollywood studios. In

1981, major studios were deeply suspicious of the new medium and

slow to get in the game, there were no big fish in the pond, only

lots of small fry. Labels like Iver Film Services, Intervision,

VTC (with their natty gold sleeves), and World of Video 2000 (which

should have been World of Video 1984, about the time it ceased trading)

sprung up and died almost overnight. With them came a wacky variety

of non-mainstream material available on the cheap.

Along side the Brotherhood of Man concert videos, Childrens Film

Foundation movies and Greek westerns that found their way into British

living rooms, was a growing number of horror movies, many continental,

and many too obscure, too dismal or too violent ever to receive

a British theatrical release. Horror films were immediately popular

on home video – and the fact that videos did not require a

BBFC certificate meant that all manner of material was available

in your local garage, corner shop or out of the back of a white

van that would never have passed the BBFC's vetting procedure had

they been released theatrically.

For a couple of years as the home video explosion continued unabated

everyone was happy, or so it seemed. The industry was Thatcher’s

free market sink-or-swim economics in a nutshell, with labels seemingly

appearing overnight and going out of business the next month, living

or dying on the quality of the product they had been able to acquire,

as all the while the big Hollywood studios stood back and watched.

It was as competition in the video marketplace grew massively and

companies began to resort to ever more lurid publicity campaigns,

when the first cracks in the new industry began to show and things

started to go wrong.

Go Video’s decision to supply Mary Whitehouse with a copy

of Cannibal Holocaust must go down as one of the greatest publicity

own-goals of all time, but it was by no means the only one. The

distributors of a little known American slasher flick called ‘NIGHTMARE’

re-named it ‘NIGHTMARES IN A DAMAGED BRAIN’

and ran a ‘guess the weight of the brain in a jar’ competition.

Astra home video released ‘SNUFF’ without

credits and with box art suggesting it was a real snuff video (which

it patently is not) and were forced to withdraw the release after

one day. Over-the-top advertising for movies like SS EXPERIMENT

CAMP and CANNIBAL FEROX in the video trade

press (and on posters outside video shops – the one in my

local town was forced to remove a poster for FLESH FOR FRANKENSTEIN

after complaints) resulted in the powers that be, pushed by the

hysterical ranting of Mary Whitehouse’s National Viewers and

Listeners Association, taking more of an interest in the extreme

end of the video market. At one point, Mrs Whitehouse complained

to the newspapers that video ‘could be the biggest threat

to the quality of life in Great Britain’. Comparing the impact

of I MISS YOU HUGS AND KISSES with the discovery

of a new and potentially devastating virus called HIV, massive levels

of unemployment, the threatened Miners Strike or the civil disorder

in places like Toxteth, Moss Side and Brixton is patently ludicrous

even without the benefit of hindsight and anyone with half a brain

could see this as rampant and groundless hyperbole based on self-publicity.

Which brings us to politicians.

It is ironic that in the same year as THE EVIL DEAD

topped the yearly video rental charts in the UK (and incidentally

the same year as a General Election – draw your own conclusions),

politicians and the mass media began a campaign to ban what euphemistically

became known as video nasties. Initially, politicians were reticent

about the industry (It was, after all both a money spinner for VAT

and a place where a daring business could make a lot of money quickly),

but organisations like the NVLA had whipped up hysteria inside Fleet

Street. Some media interests (particularly our own whiter-than-white

press) recognised the impact that unfettered growth of the video

market could have on fledgling projects like British Satellite Broadcasting

and Sky, as well as the fact that the medium was largely incomprehensible

to the generation that purchased their product. It also represented

an easy target – who could complain if their campaigns resulted

in the banning of CANNIBAL HOLOCAUST? Certainly

not readers of the Daily Mail. And so the press coverage began,

calling for violent videos to be banned or burned, asking how such

material could creep past the BBFC uncensored (in fact most movies

had never been near the BBFC – which had no remit for videos

at the time) and asking the government what they intended to do

about this new menace.

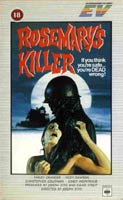

Government didn’t get time to answer. Armed with the newly

amended Obscene Publications Act, Police Constabularies across the

country began to seize videos. There was little rhyme or reason

behind these seizures, movies were taken from video shops in one

county that were left on the shelf in adjacent counties. Alongside

those movies that would eventually be identified as the ‘video

nasties’, films such as SUPERSTITION (1981),

MADMAN (1982), BLOOD FOR DRACULA

(1973), BASKET CASE (1982), John Carpenter’s

remake of THE THING (1982), DEMENTED

(1980), THE EXTERMINATOR (1980), ROSEMARY'S

KILLER (1981) and CITY OF THE LIVING DEAD

(1980) were taken in some places. Occasionally the police made some

real howlers, like confiscating copies of the Dolly Parton/Burt

Reynolds comedy THE BEST LIITLE WHOREHOUSE IN TEXAS

(1981) and Sam Fullers war movie THE BIG RED ONE

(1977) (apparently the constabularies responsible thought these

movies were porn films – though you’d have thought that

the briefest glance at the video box art would have put that right!),

but the majority of films taken were horror movies. Alarmed by the

seemingly random selection of titles and the inconsistency of seizure

between police force areas, the newly formed Video Retailers Association

begged the Department for Public Prosecutions for some guidance

for its members as to what material could be stocked and what would

be liable for confiscation. As the DPP was in the process of preparing

prosecutions against dealers and publishers of a number of films,

and recognising that the current situation was undermining the concept

of a consistent justice system across the whole country, the Department

of Public Prosecutions prepared a list of movies liable for seizure

and that had either already successfully been prosecuted or had

charges already filed against distributors and stockists of them.

This list of movies became known as the Video Nasties list.

This list, which changed in composition almost every month from

the first list being published in June 1983, is highlighted below,

with the subsequent fate of the movie also included. Altogether

some 75 titles appeared on the list at one time or another, with

a number of them changing as prosecutions were dropped, or prosecutions

failed. In total, 35 films initially listed by the DPP had to be

dropped because there was never a successful prosecution against

them, leaving the rest, 39 titles as the rump of the list. For 15

years many of these films were left in uncertified limbo by the

Video Recordings Act, which effectively put an end to the DPP list

when it came into force in 1985, by making all non-certified videos

(with some exceptions) illegal. In practice the DPP maintained its

list of 39 films until the mid 1990’s, but in the end, the

Video Recordings Act made it defunct and it quietly faded from the

scene. With the change in the BBFC regime recently, and thanks to

the positive critical reappraisal some of these movies have enjoyed,

many of the movies previously banned have been made available uncut,

whilst others have been re-released cut (sometimes because of a

recent, successful prosecution under the Obscene Publications Act

and sometimes because they fall foul of the BBFC’s new guidelines).

These movies, and their fate after being listed, are highlighted

below.

|