With the onset of niche magazines, zines and then eventually the Internet, which is overflowing with blogs and websites, fandom has embraced horror in a variety of ways. The genre has been surveyed, analyzed, critiqued, and gushed over. And, yet, while there seems to be an emphasis on different eras of the genre (the subversive 1970s, early 1980s slashers, the postmodern epoch that came with the release of Scream in 1996, etc.), very little serious attention has been given to the world of the direct to video (DTV) era that began in the late 1980s. Subsequently, although worthwhile DTV releases such as The Unnamable (1988) and Ticks (1993) remain pleasurable memories, they have not received the same kind of consideration as films from periods directly surrounding this uniquely fascinating age of discovery. And I find that very sad.

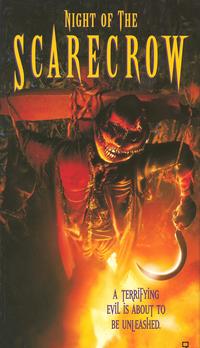

Recently, Yale established a nifty genre VHS archive, which places an academic lens on not just the movies, but also on the very boxes they are housed in. The main loci of this acquisition allows us to view the VHS tape and its container in several different ways: as a cultural artifact; as an audio-visual tour of cinefile culture of the 1980s – early noughties; and as a byproduct that tells the sometimes sordid and always wonderful tales of the early days of the home video market. Yale has damn near legitimized some aspects of the DTV era, and, yet, despite a rise in interest, Night of the Scarecrow remains a bit of an obscurity.

The unique hook of a creepy killer scarecrow, and its sincere, straight-shooting script by Reed Steiner and Dan Mazur hits most of the right beats, but the film unfortunately failed to capture a larger audience upon its original release in 1995. Yet it is probably because of its unpretentious approach that it has built up a small but loyal cult fanbase over the last two decades. Coming out the year before Scream, which ushered in the slew of self-aware horror films to follow, this no-frills supernatural entry certainly walks familiar paths, but remains fresh thanks to its cinematic quality, strong direction, and confident performances from both the seasoned and more inexperienced cast.

Night of the Scarecrow is by no means unique to that subgenre of films concerned with gothic, sleepy towns harboring a dark secret. Some of the more famous titles range from Herschell Gordon Lewis’ tawdry and enormously entertaining flick Two Thousand Maniacs (1964) to the classic Dead and Buried (1981). In these particular tales, the population is willfully clandestine, and the secret works as way to maintain a sinister status quo. In Night of the Scarecrow the community seems blissfully ignorant to the fact that the town leaders, who are a quartet of brothers, are benefitting from the violent death of a warlock who had once blessed the settlement with a fertile and prosperous field. After a random act of vandalism unearths the magician's tomb, the warlock rises from the dead, and using a nearby scarecrow to manifest into a physical form, stalks the family across one night of bloodshed and revenge.

The scarecrow makes for a neat killer but he also takes on a more metaphorical rendering of a town, and of a family, constructed through a patchwork history, where a willful disregard for the past preserves an imbalanced and dysfunctional pecking order. Like the scarecrow’s makeshift build, the mayor’s daughter, Claire (Elizabeth Barondes) has to pull together a patchwork of her own history in an effort to fully comprehend the greed that has allowed her family to continue to profit off of murder. She learns that centuries prior the town had employed the mystic powers of the warlock to help them replenish the field with the finest crops. Because of his success in restoring the town’s place in commerce, the necromancer rises up the ranks of society, and literally seduces its citizens, holding mass orgies with the locals. Not wanting to give up their cash cow, those against the warlock choose to look the other way. That is, until Claire’s ancestor is lured into a night of debauchery. Only when one of the family members is tempted into a world of sexual gratification does anyone take action, and an angry crowd drags the warlock through the streets, killing him in the field. The evils of the town are made apparent in this act: They condemn pleasure, but condone violence, and even murder.

Therefore, the setting for Night of the Scarecrow is rich with small town commentary, positioning the wealthy brothers as an oligarchy overseeing the town’s main institutions, which include government, law enforcement religion, and even oversight of the agriculture. They can make excuses for their own actions, but can also discriminate against those not in their inner circle. The siblings are jointly in possession of that field and are happy to reap the rewards of mowing it down and turning the property into a mall, further corrupting the land that was intended to benefit the entire community, not just the elite. Comprised of the more basic yokel stereotypes, the fine cast makes the most of their hackneyed caricatures: the mayor (Gary Lockwood) is the greedy “Boss Hogg” type who is only interested in profiting off a wrongful murder, the overly guilt-ridden pious priest (Bruce Glover) doesn’t know his own daughter is a tramp (and confiscates her Victoria’s Secret for his own shameless pleasure), and both the stern but flabby sheriff (Stephen Root) and the brother who runs the field (Dirk Blocker) seem more interested in having a beer than maintaining any real order in the town or in the meadow. The dynamics of the family isn’t necessarily fleshed out to anything more than suitable for this kind of film, but it certainly plays out as well as any DTV hixploitation flick should.

Admittedly, one of the bigger hiccups in Night of the Scarecrow is that it is indeed hampered just a touch by a few hinky special effects (hey, it was 1995, guys), but Burr’s genuine approach to the material reminds one of the halcyon days of seemingly unstoppable killing machines that were so popular. That’s not to say that this film is a classic like the Friday the 13ths and Nightmare on Elm Streets that came before it, but it is a film that offers more layers, and real tension, than critics have given it credit for. However, the most interesting aspect of Night of the Scarecrow is how it seems to be passing the torch between epochs. The veteran cast symbolizes the straight-faced films of the decades prior, with the younger cast more characteristic of the self-aware, rebellious films to follow. Claire is no shrinking violet. She owns her intelligence, autonomy and sexuality, paving the way for Final Girls in the more famous films of the post-modern era that was to follow shortly thereafter.

Jeff Burr is the king of economical filmmaking. Having already directed several movies before Night of the Scarecrow, Burr was familiar with both the world of theatrical and DTV releases, and worked well with varying but predominantly low budgets. His films always provide a larger, more filmic approach, and are consistently crisp, fluid and vibrant. He often collaborated with cinematographer Thomas Callaway (Pumpkinhead II: Blood Wings, Eddie Pressley, etc.), and the duo seem to bring out the best in each other in terms of creating rich landscapes that made the budgets of these little films seem much higher. But Burr also never sacrifices a good story in favor of slickness, and while low budget movies will be hampered by any number of issues, Burr’s films remain entertaining, and Night of the Scarecrow deserves a larger audience.

Amanda Reyes is a freelance writer and podcaster who focuses on the made for television movie genre with her blog Made for TV Mayhem and its companion podcast.

Keep Hysteria Lives! alive. Donate: https://paypal.me/hysterialives.