NIGHT OF THE LONG KNIVES AT CAMP BLOOD: HOW KILLER CRITICS TRIED TO MASSACRE PARAMOUNT'S BIGGEST HORROR HIT OF 1980 (by JA Kerswell)

Today – no pun intended – the campier aspects of the original FRIDAY THE 13TH (1980) are celebrated through a warm haze of nostalgia. For many – me included – it is almost a 'comfort horror'. However, it is worth remembering that it was one of the most controversial films of the year it was released. For many critics it was public enemy number one. To modern eyes, the pure vitriol poured on Sean S. Cunningham's movie might be surprising – if not a little shocking. But FRIDAY THE 13TH was so divisive that it created a watershed moment that both boosted, and paradoxically neutered, the burgeoning slasher movie craze.

|

Perhaps surprisingly, the success of HALLOWEEN (1978) – itself an independently released sleeper hit – did not immediately initiative a crimson tidal wave of imitators in 1979. There was the South African lensed THE DEMON (which wasn't released to North American screens until years later as MIDNIGHT CALLER in 1985). However, both SILENT SCREAM and WHEN A STRANGER CALLS (both made before or around the time HALLOWEEN was released) somewhat accidentally tapped into an audience that was hungry for for more of what John Carpenter's movie had given them. Joan Harris, producer of SILENT SCREAM, said in 1980: “The horror genre is the only genre that hasn't faded. Ever since silent movies, there has always been horror. While motorcycle movies and beach party movies and '60s protest movies all died - the horror movie lived.” Both films were not particularly graphic and garnered generally favourable reviews from critics. Both were also surprise hits – with Fred Walton's WHEN A STRANGER CALLS filling the lucrative October horror hotspot in 1979 and generating huge profits for major studio Columbia Pictures (which distributed the independently produced movie to screens across North America). Columbia Pictures' promotional efforts for the film focused exclusively on the elements that most clearly mirrored those in HALLOWEEN. The interest of other major studios was instantly piqued. Horror was on the ascendent and Walton's film had shown that low-to-medium budgeted independently produced genre films could generate big profits once they had the promotional might and national screen reach of a major studio behind them. No one could have predicted just how successful commercially – and nearly ruinous for their reputation – Paramount releasing a little terror flick called FRIDAY THE 13TH would be in the spring of 1980.

Some movie analysts referred to 1980 as the year that “Hollywood bottomed out” after a steady decline in box office throughout the 1970s. So much so that the word was that some producers welcomed an actor's strike as a way of cutting production costs. Major studios were especially spooked by the commercial failures of recent high profile flops. That made the likes of FRIDAY THE 13TH very attractive to Paramount – who saw it as a 'low risk' release financially and paid $1.5 million to acquire it (three times what it cost to make). So keen on the prospects of the film, Paramount pumped $3 million into promoting it (five times its production costs). Frank Mancuso, then senior vice president of distribution at Paramount, said that word-of-mouth did the rest. There was a view that Hollywood stars had priced themselves out and there was a whole generation of unknown, hungry young actors just waiting for their chance. A spokesperson for Lorimar (who announced they were planning to double production on genre projects in 1981) said of horror movies: “They're easy to advertise and easy to sell … And that's the key to this business. You can't make money on noble failures.” By November of 1980, Variety noted that 40% of revenue generated on North American screens came from horror and sci-fi movies. 1980 saw 84 horror movies shot in North America and Canada (rising to 110 in 1981). Paramount beat out interest from Universal Studio and Warner Bros for FRIDAY THE 13TH (although the latter secured international release rights). These independently produced, low budget 'terror flicks' (as they were often dubbed back then) came fully formed and without the headaches involved in making them directly. Although it resulted in a headache of an altogether different kind for Paramount.

|

It is difficult to pinpoint just one element that caused the critical backlash against FRIDAY THE 13TH. But a number of things contributed. Perhaps most notably it was the feeling that it was beneath a major studio such as Paramount to release a gory horror film. And not just release it, but do a saturation release to over a thousand screens across North America. There was a definite snobbery amongst critics at the time. Whilst most would tolerate exploitation horror confined to the relative ghettos of the likes of 42nd Street in New York or drive-ins they were outraged that FRIDAY THE 13TH had broken out of such ghettoisation and had hopped into the mainstream. After all, it was hardly the first film to feature graphic gore. Herschell Gordon Lewis had pioneered gore in movies as far back as 1963 with his seminal BLOOD FEAST. This had sparked a good number of imitations throughout the 1970s, with a film such as the proto-slasher SCREAM BLOODY MURDER (1973) promising audiences they would: “See GORE-NOGRAPHY for the first time.” Director George A Romero – who also pioneered gore in movies with NIGHT OF THE LIVING DEAD (1968) and DAWN OF THE DEAD (1978) talked about why the slasher movie was so attractive to both independent producers and major studios looking to pick up a bargain in 1980: “You don't need much to make a horror film. We made Night' for $60,000. All you need is a little bit of makeup, a deserted house, a few knives and a camera … You can make a fortune with a small investment. When investors put up money for a film they like that sort of security.”

Intentional or not (almost certainly not) FRIDAY THE 13TH was accused of both liberalism and conservatism. The envelope pushing violence was seen as ripping up moral norms for mainstream cinema and was presented as evidence of moral decline and, somewhat hysterically, as a danger to American youth. There was the inherent snobbery of the mostly middle-class mainstream critics that young, working class audiences would be warped by such films – as if they were somehow less intelligent and more susceptible to corrupting influences. On the other hand, FRIDAY THE 13TH was also accused of being regressive with its sexual politics – with the idea that it was a rebuke to the permissive 1970s and that premarital sex was something to be punished (in the most brutal ways imaginable). This completely missed the point that sex and horror sells. It always has. It wasn't making a profound point. Cunningham, ever canny, was simply ticking off the checklist from the exploitation manual. Also, increasingly critics lambasted FRIDAY THE 13TH (and many of the films that followed) of actively hating women. The charge was that it gloated in the terrorisation and onscreen murders of its female cast – ignoring that, if anything, Cunningham's film featured equal opportunities misanthropy. There are arguably some slasher movies from the time that have misogynistic leanings, but FRIDAY THE 13TH isn't one of them. Men were fair game, too, and died in equally brutal ways. And, of course, the killer in FRIDAY THE 13TH is female – as is her last standing opponent.

|

There was also a growing feeling amongst mainstream critics that movies were just simply going too far. WINDOWS – where a woman is terrorised by her lesbian neighbour – was released in January 1980 (and quickly vanished after the controversy it attracted). The Unrated release of the infamous CALIGULA – which featured hard core porn scenes – had scandalised critics in February of 1980. As had William Friedkin's CRUISING (also released that February). To add fuel to the fire, sleazy slasher roughie DON'T ANSWER THE PHONE was released to screens around the same time – as was DON'T GO IN THE HOUSE. The tinderbox was bone dry and it didn't take much to ignite a fresh controversy with FRIDAY THE 13TH on its wide release in May 1980. Lastly, but perhaps just as importantly, mainstream critics found themselves impotent. The film was critic proof and glided easily into massive profits for Paramount (it took nearly $40 million at the US box office – the equivalent of over $140 million in 2022). This seemingly enraged them.

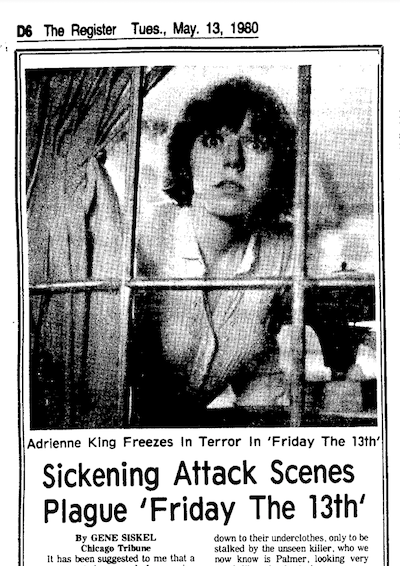

Leading the charge against FRIDAY THE 13TH were review double act Gene Siskel and Roger Ebert from the Chicago Tribune and Chicago Sun-Time respectively. Unlike other film critics of the time the pair had even greater reach through their syndicated TV show Sneak Previews. They infamously near as published the home address of actress Betsy Palmer (who played the killer Mrs Voorhees) to berate her for appearing in the film. In this they conveniently ignored the fact that many veteran actresses had appeared in low budget horror movies in the twilight of their careers – from Joan Crawford to Rita Hayworth. Often – somewhat uncharitably – termed as 'hag horror'. Palmer was undoubtedly bemused by all this at first (she latter admitted it upset her greatly). She admitted she made the film because she needed a new car and told anyone who would listen that she didn't think “That piece of shit would ever see the light of day” (she mellowed considerably later when she realised what a following the series – and her character – had ). Gene Siskel attempted to spike the film by revealing who the killer was in his review in The Chicago Tribune. He wrote: “Now there – I hope I ruined Friday the 13th, which is the latest film by one of the most despicable creatures to infest the movie business, Sean S. Cunningham.” Siskel ignored the male victims in his review and said Cunningham's speciality was “... that old, sick standby, teen-age girls in peril.” He finished by asking readers to send their outrage to Betsy Palmer and the chairman of Gulf and Western (Paramount was at that time a subsidiary). Bob Martin, of Fangoria Magazine, encouraged readers to undertake a rival letter-writing campaign to Siskel to complain about his approach (although he claimed never to have received any letters). With the religious verve of witch-finder generals, Siskel and Ebert became ever more hysterical and pearl clutching in their outrage with FRIDAY THE 13TH and other horror films released in the early 1980s. The language they used became ever more inflammatory. They accused the makers of FRIDAY THE 13TH and other similar movies of pitting “liberated” women against maniacal killers. They said these women were defenceless (ignoring the fact that the typical 'final girl' was anything but defenceless and usually saved the day and herself in a role reversal of the usual male saviour trope). In a report in trade magazine Variety in November 1980, the duo said these modern horror films were “gruesome and despicable” – even lumping in WHEN A STRANGER CALLS and SILENT SCREAM – as “expressing a hatred of women”. Siskel said that these films were a reaction to the feminist movement that told women “to get back in their place or be sadistically murdered”. They also railed against the MPAA for passing movies such as FRIDAY THE 13TH with an R rating – and insisted they should be issued with an X rating (and essentially banished from mainstream cinema). Siskel also levelled the claim that the MPAA were lenient on the film (although they did cut 9 seconds for an R rating) because Paramount paid part of the salary of the censor board. Ebert was especially bothered by the point-of-view camera that he said gave the audience the eyes of the killer and might even encourage an increase in violent urges in susceptible people (although presumably not high-falutin film critics). Again, the POV is not a new technique and has been used in psycho thrillers as far back as Robert Siodmak's THE SPIRAL STAIRCASE (1946). In a chilling foreshadowing of the 'video nasty' debacle that exploded in the UK a few years later, Siskel came close to suggesting that gore movies should be banned altogether; comparing them to bullfights as an affront to decency and morality (I agree with him on bullfights at least!). Their approach was disingenuous, as they cherry-picked elements they wanted to condemn whilst ignoring inconvenient truths (that men were also victims for example). Ebert surely knew what he was doing when, in his review of FRIDAY THE 13TH PART 2 a year later in May 1981, he wrote: “The original Mad Slasher movies were mostly anti-woman; this movie kills young men, too.” They also knew that many of the people who would have written to Paramount to condemn the release of the film wouldn't have actually seen it. After all, Siskel and Ebert had told them not to – and whatever they thought FRIDAY THE 13TH would be was surely far worse in their minds than the reality. This stoked the myth that slasher films of the early 1980s were routinely – and dangerously – misogynistic. Along with The Chicago Tribune, The Chicago Sun-Times boasted they banned salacious press adverts for horror movies in an effort to lessen their commercial appeal. FRIDAY THE 13TH appeared in both papers in text only listings – despite the film never being advertised in any way sexually. In fact, the advertising for FRIDAY THE 13TH was remarkably restrained.

|

Director Wes Craven, who Variety noted was about to begin work on DEADLY BLESSING in early 1981 was one of the few voices to defend the horror genre in 1980 and dismissed the criticism of the likes of Siskel and Ebert as far too simplistic. He said that horror film crowds of that year tended to come from lower economic classes and noted that they had a clearer awareness of social problems than middle or upper classes. One of the things that Ebert railed against was horror movie crowds cheering on the gory mayhem on screen – which he said disturbed him more than anything. Craven told Variety: “The reason audiences at horror pix often seem to be amused by bloodshed is it's a way to exorcise horror. They know it's syrup not blood, and that's a plastic axe in her hand. I can certainly tell you that in the cutting room there's a lot of laughing going on.”

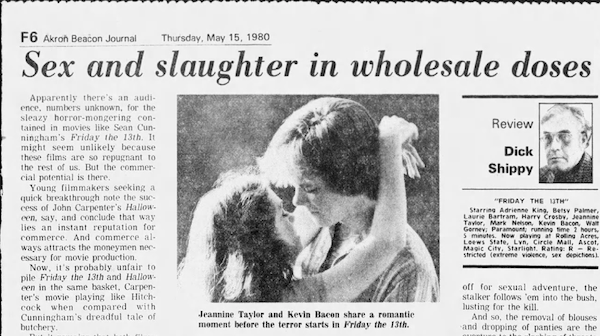

However, Siskel and Ebert were certainly not alone with their hyper criticism of FRIDAY THE 13TH (although they were by far and away the most outspoken). Janet Maslin, of The New York Times, also gave away the identity of the killer in the first line of her review in an effort to put audiences off (although she did begrudgingly admit some of it was suspenseful). Variety dismissed the film in its review: “... low budget in the worst sense – with no apparent talent or intelligence to offset its technical inadequacies.” Most critics dismissed it as a blatant rip-off of HALLOWEEN – but with added ultra violence. The critic at the Des Moines Tribune joked he would want “combat pay” to sit through another film like this. The joking stopped when he or she referred to it as “... not a thriller, it's a massacre. It's an SandM show – sadism for you, and masochism for you, too.” John Omwake in the Kingsport Times-News gave the film a back-handed compliment: “Blood flows by the bucketful in “Friday the 13th,” a sometimes scary but mostly repulsive horror movie.” Keith Roysdon in the Evening Press worried that audiences wouldn't be prepared for how realistic the murders looked in the film, but begrudgingly acknowledged “the audience seemed to be having a great time.” The Pensacola News Journal led with the headline: “This movie should be rated 'N' for 'nasty'”. The Akron Beacon dismissed the film as “Sex and slaughter in wholesale doses”. Whilst The Shreveport-Bossier Times couldn't understand why it was proving to be such a big hit with audiences. Lane Crockett, that's paper's film critic, bemoaned: “This kind of rip-off trash doesn't speak well for films and neither does it for filmgoers.” He also attacked Palmer for “sinking this low” by appearing in the film. The Lincoln Star dismissed it as a “turkey”. The following year, both the film and Betsy Palmer were nominated for the infamous Razzie Awards. The controversy around the critical reaction to FRIDAY THE 13TH led to some mainstream critics refusing to review what they termed 'maniac films'. The Daily Herald's Dann Gire responding to criticism from a reader (who was defending slasher movies as escapist fun) said in 1981: “A blanket “no stars” policy to a maniac movie, one that exists solely as a parasite to an earlier work and utilizes people as mere animals in a butcher shop is indeed a fair and just one.”

|

It wasn't just the critics turning on gory horror movies in 1980. Even distributers were expressing their concerns. At the MIFED event in October of that year, Bill Moraskie of Carolco said: “All they want is blood pouring off the screen. I question the mental balance of the people making and buying this stuff.” Another buyer, Tony Birley, was even more brutal in his assessment: “The old Hammer stuff was good clean horror which could not be related to real life. Now sadistic horror which can be emulated is the vogue. … There's one film here that was obviously made by the mentally defective for the mentally defective.”

|

Victor Miller, who wrote FRIDAY THE 13TH, was just as stunned as anyone that the film had been such a runaway success. A – slightly tongue-in-cheek – piece he wrote in the Washington Post in June 1980 carried the headline: “Writer accepts consequences of 'Friday the 13th'”. He said: “I wrote one of the more frightening and gory movies ever made. Now I have to deal with the consequences.” He said he was nervous about his parents seeing the movie, but his mother declared it “... a marvellous parody of horror movies.” Miller admitted he had never seen a horror movie before, so was somewhat surprised to be asked to write FRIDAY THE 13TH by Sean S. Cunningham. Cunningham told him: “I have $500,000 to make a very scary film that should grab as large an audience as possible.” Together they came up with the concept and the kills – although Miller says the ideas were mostly his (even back then they couldn't agree on this). He said he had been invited to schools to talk to students (who had all seen the film) and had to reassure them he didn't have weapons in his suitcase. The somewhat jokey nature of article evaporated when he noted that although the movie was “critic proof” he was not. “I have written a blockbuster and all my dreams have come true. It really does hurt to have to deal with the incredible vitriol that has come my way since we opened on May 9.” He condemned the Siskel review that essentially published Betsy Palmer's home address: “With all the loonies loose in our society, can anyone condone that little trick?”. On why the film had attracted such vitriol Miller concluded: “In short, Friday the 13th seems to have pushed a button in the critical solar plexus producing not just negative reviews, but rage.”

|

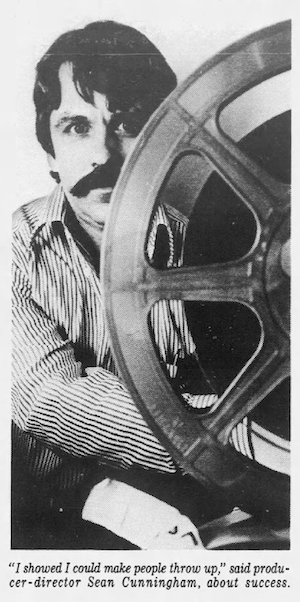

Cunningham more-or-less admitted to Fangoria that he wanted to repeat the success of Carpenter's HALLOWEEN but with the graphic gore of Romero's DAWN OF THE DEAD (1978). Which – with the involvement of Tom Savini – is pretty much what he got. Ever the businessman, Cunningham knew he needed a bit of extra carny trickery to stand out from the crowd. Adding to the gore was a healthy pinch of the low-brow hi-jinks of the likes of NATIONAL LAMPOON'S ANIMAL HOUSE (1978) and the similar shenanigans and the borrowed location of SUMMER CAMP and the surprise box office smash MEATBALLS (another lucrative independent pick up for Paramount) (both 1979). When asked if he was bothered by the bad press he said: “Are you kidding? It's all very nice to talk about the 'art of cinema', but in this business you need a hit to survive.” He noted that the film had opened multiple doors to him in Hollywood. On being asked what was the secret of his success – FRIDAY THE 13TH was second only to THE EMPIRE STRIKES BACK at the North American box office in the summer of 1980 – Cunningham joked: “I showed I could make people throw up.” He said he expected the critical mauling, but defended the movie. He told the LA Times in June 1980: “If people think it's easy to scare an audience, they're wrong. The reason my film is so successful is that it succeeds at exactly that level. If it was that easy to do, more films would do it.”

Not every critic hated FRIDAY THE 13TH. Lou Gaul in Daily Intelligencer compared it to a rollercoaster, but noted its magpie nature. He said: “Viewers who just like pictures to leave them screaming for more will want to get right in line for this one.” Chronicle Telegraph staff writer Kathryn Buchanan wrote: “It seems almost embarrassing to say this is good entertainment.” Ken Love in the Olathe News gave it a semi-positive review: “Special effects are outstanding. Never has violence appeared so real.” He saw its commercial appeal and said the R rating wasn't putting off kids: “The theater was packed with row after row of bubble-gummers.”

However, some of the critical poison pen letters did have an effect. The MPAA in the United States and the BBFC in the UK were stung by the criticism that they were too lenient with FRIDAY THE 13TH. The BBFC let the film through completely unscathed for its UK theatrical cinema release (the US R-rated version was shorn of nine seconds of gore for the North American cinema release). Chief censor at the time, James Ferman, said it was “So far-fetched … that it was clearly unreal”. However, the era of stringent censorship was just around the corner – in both cinema and on video. In fact, the film – after its British unrated pre-cert VHS release in 1982 – remained unavailable on video until 1987 (which was a censored version and it took until 2003 for the uncut version to be passed in the UK). The irony was – of course – producers who wanted to top FRIDAY THE 13TH for violence were stymied by increasingly orthodox, and politically influenced, censorship regimes. Whilst Cunningham's film provided the bloodshed it also unwittingly caused a watershed and a clampdown of what was acceptable in terms of gore in R-rated movies. Paramount – who were keen to milk their cash cow – found themselves in endless battles with the censor board over FRIDAY THE 13TH PART 2 (which suffered 48 seconds of cuts) and MY BLOODY VALENTINE (both 1981).

As Variety noted in late 1980, the horror bubble was already showing signs of bursting. They compared it to the giallo boom that lasted a few years in Italy after the release of Dario Argento's THE BIRD WITH THE CRYSTAL PLUMAGE (1970). It is arguable whether films such a MY BLOODY VALENTINE would have been more successful had they been released uncut as intended (although that certainly wouldn't have hurt their chances). By 1982, of the 140 horror films announced only 45 were made (and many remained unreleased that year). However, the FRIDAY THE 13TH series continued to make money right through the 1980s. The irony being, of course, it ultimately wasn't Siskel and Ebert that killed the franchise – rather the interminable legal battles between Sean S. Cunningham and Victor Miller.

Thank you for reading! And, if you've enjoyed this article, please consider a donation to help keep Hysteria Lives! alive! Donate now with Paypal.